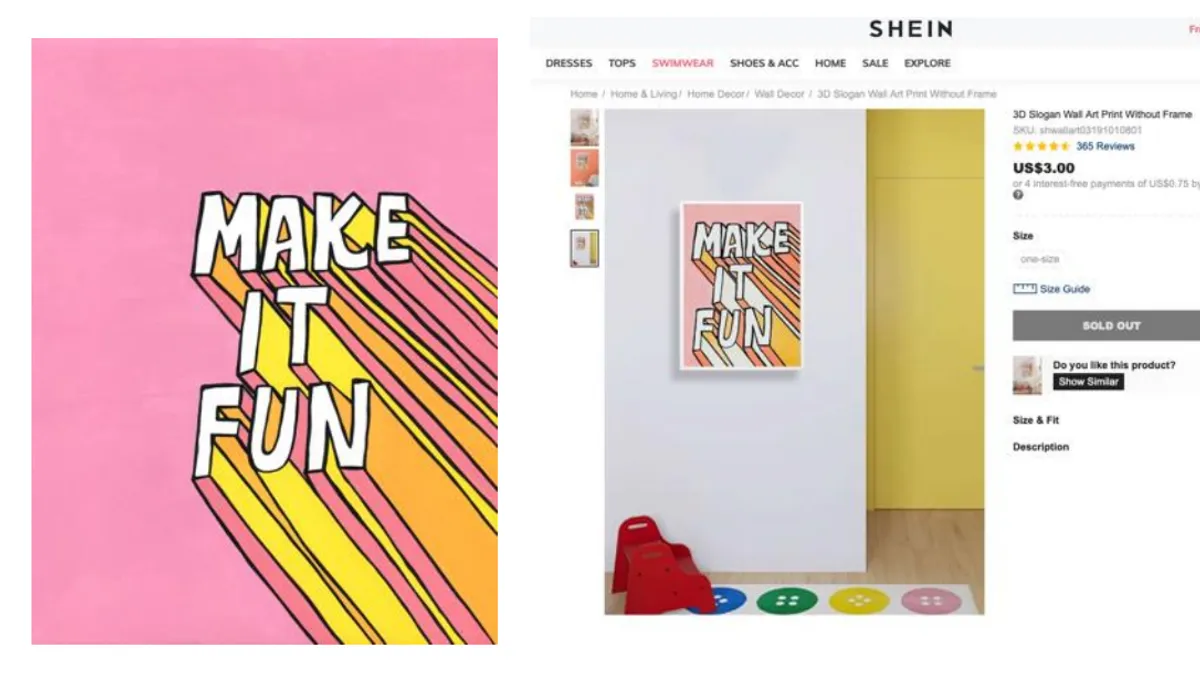

Independent designers Krista Perry, Larissa Martinez and Jay Baron this week sued Shein, alleging that the e-commerce giant “produced, distributed, and sold exact copies of their creative work.”

The lawsuit is brought under the civil portion of the racketeering law known as the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization Act, or RICO, per court documents.

A Shein spokesperson said by email that the company “takes all claims of infringement seriously, and we take swift action when complaints are raised by valid IP rights holders. We will vigorously defend ourselves against this lawsuit and any claims that are without merit.”

As Perry, Martinez, Baron and their lawyers note in their lawsuit, Shein’s corporate structure and production strategy make it difficult to pin it down.

The e-commerce giant’s “intellectual property theft and blame avoidance is facilitated by its byzantine shell game of a corporate structure,” they write in court papers.

Pursuing Shein down on copyright or trademark grounds is complicated because the company produces small runs of designs that its algorithm finds and determines will sell out of relatively few copies, according to John Conway, CEO of Astonish Media Group and an attorney whose specialties include intellectual property issues. That means a potentially expensive lawsuit that, if successful, might yield little reward. In addition, Shein is not a conglomerate in any traditional sense, but rather a shifting confederacy of entities — many of which are here today and gone tomorrow, he said by phone.

“So you don't know who's actually doing the copying,” Conway said. “That's why I think it's interesting that they brought a RICO complaint — which is for organized crime — that all these companies are in on this big scam. That also entitles the plaintiffs to more profits, if they can prove it. The real money is going to come down to RICO. And is that going to be enough money to stop or slow down Shein? That remains to be seen.”

Furthermore, rather than a creative director or chief merchant, the designers name “a mysterious tech genius, Xu Yangtian aka Chris Xu, about whom almost nothing is known.”

“He made Shein the world’s top clothing company through high technology, not high design,” they said in court papers. “The brand has made billions by creating a secretive algorithm that astonishingly determines nascent fashion trends — and by coupling it with a corporate structure, including production and fulfillment schemes, that are perfectly executed to grease the wheels of the algorithm, including its unsavory and illegal aspects.”

This has implications for copyright and trademark questions emerging as AI takes off, according to Shubha Ghosh, professor at Syracuse University College of Law. Like Conway, Ghosh believes that the RICO angle, while unusual, may be an effective avenue.

“You have to somehow figure out the best way, legally, to aggregate all those individual acts into something that's a basis for liability,” he said by phone. “The allegations are fairly compelling. Not to mention some issues regarding what's called extraterritoriality — going after things that might be happening overseas. It's a very interesting case, so I think it has legs. I don't know how far it'll run.”

The RICO laws may not help that much in the end, according to attorney Alan Behr, chairman of the fashion and luxury practice at law firm Phillips Nizer.

That’s because there may be problems with some details in the lawsuit itself. For example, in some cases, copyright or trademarks were registered just a few months ago, which may be too late if Shein stopped selling the items in question. In other cases, numbers listed with the registrations were inaccurate, Behr found.

“Maybe there's a claim, but you have to plead in a more precise way,” he said by phone. “And it's hyperbolic. You’ve got be careful with hyperbolic complaints because none of the hyperbole is legally actionable.”