New York’s EPR for packaging bill did not pass before the end of the state’s formal legislative session, marking another year where the high-profile bill gained last-minute momentum but did not make it over the finish line.

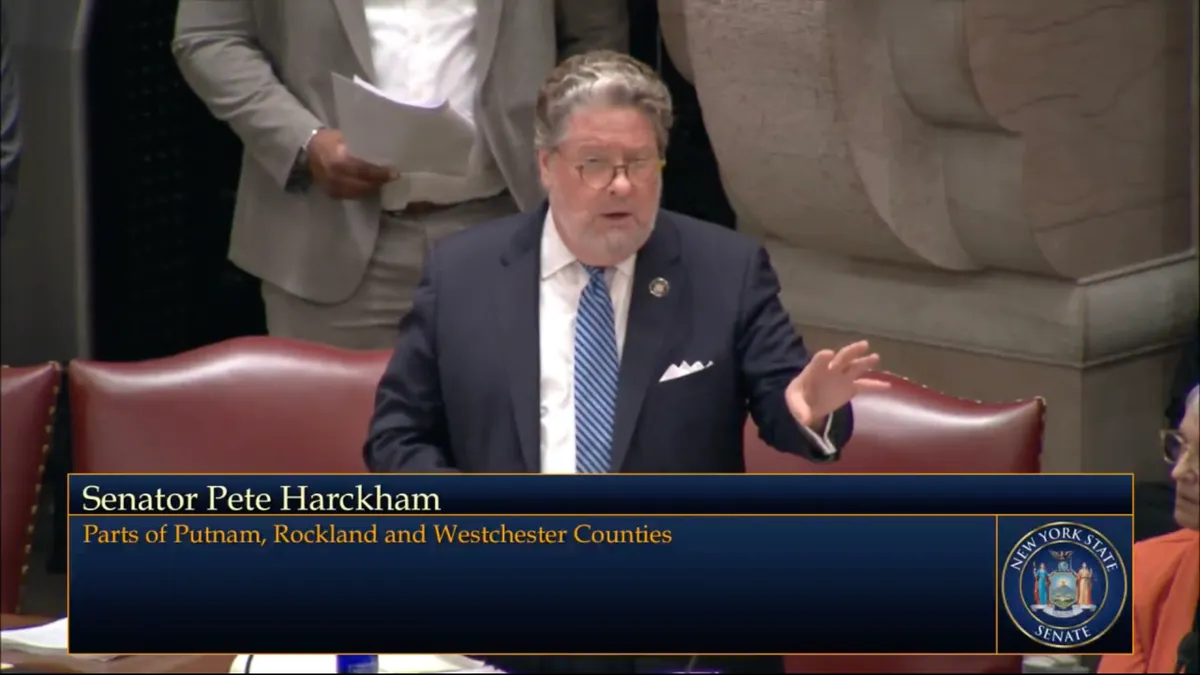

The Packaging Reduction and Recycling Infrastructure Act, sponsored by state Sen. Pete Harckham, passed the state Senate 37-23 last Friday afternoon. However, the state Assembly did not bring the bill to a vote before it adjourned.

The bill was meant to fund state recycling efforts and ban certain chemicals in packaging as well as set recycled content requirements and plastic reduction thresholds.

The legislation has been heavily debated in recent weeks, with support from advocacy groups such as Beyond Plastics and opposition from industry groups such as the American Chemistry Council and the National Waste & Recycling Association. New York City’s Department of Sanitation and local elected officials supported it. According to Harckham, New York City projects it could save $150 million per year in waste and recycling costs from the law, and other parts of the state could save $100 million.

Lawmakers and supporters in New York have worked for years to pass some version of EPR for packaging, but the complex bill has typically stalled due to conflicting priorities from stakeholders and opposition groups.

Harckham said this year’s bill went through multiple amendments in an effort to appease industry concerns. Changes included using the preferred producer responsibility organization model of industry-led groups and adding flexibility for how they can meet certain targets. He also said the bill would not affect waste and recycling contract structures, and “nothing that the PRO decides will override those contracts.” Harckham also said it could spur market development and cited shrinking disposal capacity as a motivating factor.

“We have a massive waste crisis, our landfills are closing,” he said.

Judith Enck, president of Beyond Plastics, said the group was happy the bill passed the Senate and said the group would be “reassessing next steps” for the coming year. She thanked Harckham and Assemblymember Deborah Glick for their support.

Lew Dubuque, NWRA’s vice president of the Northeast region that includes New York, said the bill would have increased costs in the state. He also expressed concerns that a statewide needs assessment wouldn’t be completed in time to provide details necessary to drafting key bill details.

“EPR programs are complicated and need to be carefully thought through, not passed in the closing hours of session after a flurry of amendments have been made to cater to many different special interests,” Dubuque said in an email.

Had the bill passed, New York would have become the sixth state to adopt EPR for packaging. Maine was the first in 2021, then Oregon. In 2022, Colorado and California followed suit. No new programs made it through in 2023, though Maryland and Illinois passed study bills. This year, a fifth state broke through in getting an industry-supported bill across the finish line: Minnesota.

New York’s Senate also passed a mattress EPR bill on Friday, but that bill similarly did not come up for a vote in the Assembly. A version of the bill had also passed the Senate last year.

Meanwhile, bottle bill advocates were also unsuccessful in a bid to increase deposit values and the scope of containers accepted.

The state’s standard deposit value is 5 cents. The bottle bill update this year sought to increase that to 10 cents per container. It also would have raised the handling fee from 3.5 cents to 6 cents. It aimed to expand the list of allowable containers to include more bottled non-carbonated beverages, such as coffee, tea, wine and liquor products. New York’s bottle bill dates back to the 1980s, but it was most recently updated in 2009.

What the EPR for packaging bill contained

The proposed legislation called for packaging producers to join a producer responsibility organization, called a “packaging reduction organization.” Fees from the program would fund state recycling infrastructure and help improve collection, reuse and other recycling-related efforts.

The bill would have banned some types of intentionally added toxic substances, such as PFAS, and materials in packaging.

The bill also set postconsumer recycled content targets for certain products, which would have gone into effect within two years of the law going into effect:

- Glass containers manufactured in the state: at least 35%.

- Paper carryout bags sold or offered in the state: 40%; unless the bag holds eight pounds or less, then the target would be 20%.

- Plastic trash bags sold or offered in the state: 20%.

- Items not listed in the bill: The state would have worked with a packaging reduction and recycling advisory council to determine rates for other kinds of items. It would have also been able to modify post-consumer recycled content targets for listed items.

The bill also set recycling rate targets:

- 25% of plastic packaging must be reused or recycled by 2029, rising to 50% by 2036 and 75% by 2051.

- 35% of non-plastic packaging must be reused or recycled, with at least 5% of that reused, by 2029. In 2036, 50% must be reused or recycled, with at least 10% reused, and by 2051, 75% must be reused or recycled with at least 20% reused.

The bill specified that recycling does not include “energy recovery or energy generation by any means, including but not limited to, combustion, incineration, pyrolysis, gasification, solvolysis, or waste-to-fuel,” as well as “any chemical conversion process” or “landfill disposal.”

The bill called for achieving reductions by eliminating single-use packaging or transitioning reusable or refillable packaging. These targets are lower than what was proposed in prior versions.

Producers would have also needed to reduce the amount of “primary plastic packaging material” in products they sell or distribute in the state by up to 30%, according to the bill.

The bill also called for that 17-member advisory council to include members representing local governments; environmental and environmental justice organizations; waste disposal or recycling associations; MRF operators; recycling collection providers; packaging manufacturers that use postconsumer content; and labor organizations that represent recycling and waste workers.